The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (described as clades Variana, the Varian disaster by Roman historians),

better known as Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald, Hermannsschlacht or Varusschlacht in the german language,

took place in 9 AC, when an alliance of Germanic tribes led by Arminius (German: Armin - also known as "Hermann"),

the son of Segimerus (German: Segimer or Sigimer) of the Cherusci, ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions,

along with their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius Varus.

Despite numerous successful campaigns and raids by the Roman army over the Rhine in the years after the battle, the

Romans were to make no more concerted attempts to conquer and permanently hold Germania beyond the river.

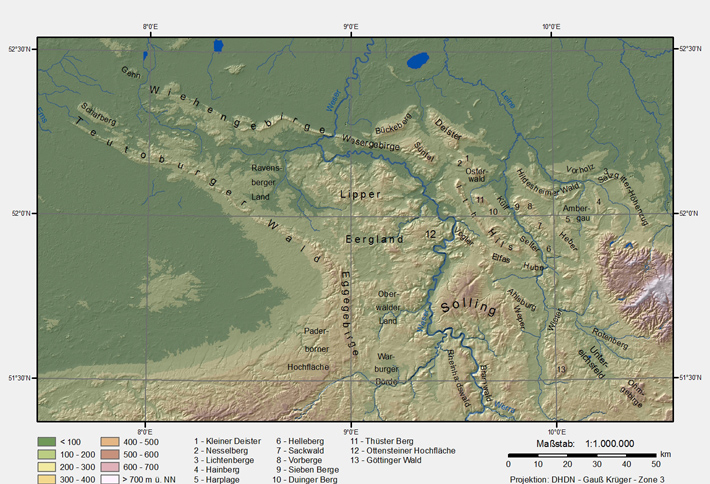

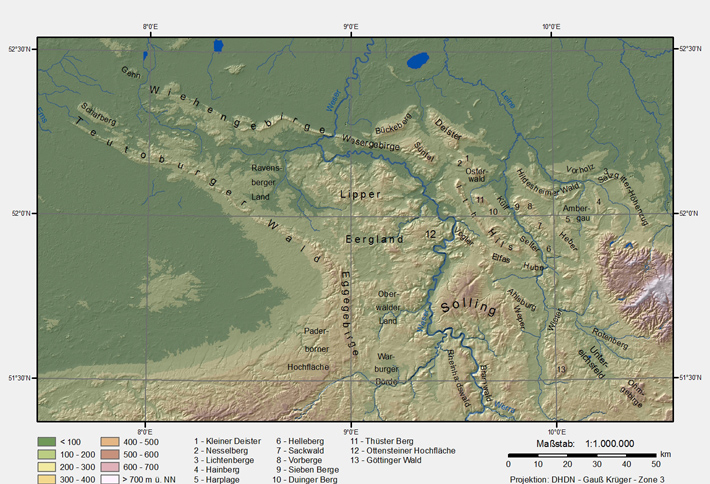

Right, my hometown Preußisch Oldendorf is situated right next to the battle field where thousands were slaughterd down 2000 years ago.

The woods and hills of the Wiehengebirge (which belongs to the Teuteburg Forest) in the south, wet and dangerous

swamplands in the north and between just a tiny corridor of sometimes just 100 m of safe land in between makes it a

perfect place for a little group of brave souls to defeat the giant Roman army which was trapped in this corridor.

The Hermann monument in Detmold in winter

The Hermann monument in Detmold in winter

But let us start from the beginning! In the last two decades BC the Romans have entered step by step into Germania.

At first, many indigenous tribes had defended themselves but were consequently suppressed. Others concluded peace

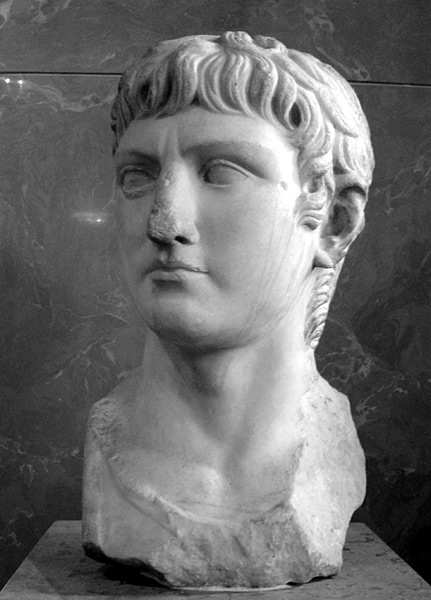

treaties and enjoyed the achievements of the Roman culture. Since 7 AD Germania had a "proper" governor,

just like any other regular province of the Roman Empire. His name was Publius Quintilius Varus and he was a much

respected man in the capitol Rome and last but not least, he was experienced: A few years earlier, he had already

been a governor of the rich province of Syria. Violent riots arose after King Herod's death - who had been the King

of Palestine. Varus brought the province under control, punished the rebels and re-established the structures of

power. He surely was the right man for Germania where the Romans occasionally encountered some resistance.

Though evil tongues said that above all he personally enriched himself in Syria. But who has success is also

the object of envy.

A coin with Publius Quintilius Varus' image

A coin with Publius Quintilius Varus' image

In the past years Varus had begun to introduce the Roman jurisdiction to Germania. He travelled around and

held court days regularly. The local tribes seemed to become accustomed to this slowly and many responded to

this offer gladly. Not quite so popular was the topic "taxes". Just like any other province, Germania was liable

to tax, too. Varus did his best to put this into action. In doing so however, incomprehension and sometimes even

hatred struck against him. However, resistance was completely futile: For the subdued provinces, the duty was

obligatory and the necessity of taxes should be clear to even every child of the Roman Empire.

After a mainly unspectacular year - with only a few skirmishes here and little grumbling of the local people

there - Varus thought he had completed his duty in Germania for this year. He and his followers started to make

their way back to the river Rhine. The route was familiar; no particular incidents happend until now.

However, Segestes (father of Arminius' wife and brother of Arminius' father Segimer), who had a good reputation

and was well regarded by the Romans, visited Varus in the evening.

Segestes was worried and tried to warn Varus of an imminent attack. He had heard reports of a local rebellion

somewhere west of the Weser river. He claimed Arminius to be the head of the rebells!

[Note: Despite recent findings indicating a Roman presence near the modern city of Minden, the location of the local

rebellion Segestes spoke of remains unclear; other sites near Minden or Rinteln have been suggested by the historian

Hans Delbrück (1848–1929) and the military writer Kurt Pastenaci (1894–1961), respectively. Anyway, this is exactly

the area of my hometown!]

The Battle Field

The Battle Field

But Arminius was an officer in Varus' own army, resting in a tent just a few yards away!

Plus, Varus knew Arminius and his father Segimer, both noble Cherusci and in possession of Roman citizenship, for a long time.

Every now and then, they dined together and he had never heard complaints about Arminius' performance as an officer

in the Roman Army, neither did he himself have a reason to complain. After all, Arminius had grown up and was educated

in Rome. His military career was promising. He had even been accepted to the Roman equestrian class.

Why should he, Varus, be endangered by this man who had grown up with Roman values and within the Roman culture?

That had to be a misunderstanding or even slander. Varus trusted Arminius completely. He shrugged and rejected the

warning.

What has happened there? It may sound like a screw-ball comedy, but amongst the Germanic tribes who didn't want to

pay taxes for their own land were the Cheruscis. And exactly this tribe started the local rebellion west of the

Weser river Segestes talked about. Segimer was the legal king of this tribe, but he was a Roman now.

He loved the life he had in the Roman capital with all the luxury around him. And so did Arminius, his son.

But patriotismn kicked in now - his Germanic people needed help! He and his son were ready for action against

the Roman Empire. But the time hadn't come yet...

Segestes himself was just worried and in panic. He was loyal towards the Romans and didn't want to risk his

life in luxury. So he was ready to dump his family. At the very end he was sucessful but not now...

Back to the story: Varus received a message a day after Segestes visit. A Germanic tribe was in difficulties and asked

for help not far away from the travelling route. This faked message was from Arminius himself! He wrote it after he

became aware of Segestes' action the night before and gave it to a local farmer with the order to bring it back to the

Roman camp.

Varus quickly calculated the detour, decided that it was acceptable and took the route into unknown territory in order

to assist the people seeking help. A fundamental mistake! Varus should have known that hardly nobody of the Germanic tribes

could write or even would have a sheet of paper. And even worse, he send out Arminius under the pretext of

drumming up Germanic forces to support the Roman campaign, because he knew the local language. Arminius left

(smiling I guess) towards his Germanic tribe and Varus entered the forest. Although moving forward through

the rough terrain was difficult - trees had to be cut down and smaller obstacles had to be overcome - all in all,

they got on rather well

The "Hermann's path" at autumn

The "Hermann's path" at autumn

Let's summarise: Varus's forces included three legions (Legio XVII, Legio XVIII, and Legio XIX), six cohorts of

auxiliary troops (non-citizens or allied troops) and three squadrons of cavalry (alae), most of which lacked combat

experience with Germanic fighters under local conditions. The Roman forces were not marching in combat formation,

and were interspersed with large numbers of camp-followers. As they entered the forest (probably just northeast

of Osnabrück), they found the track narrow and muddy; according to Dio Cassius a violent storm had also

arisen. That was the beginning of the end!

The line of march was now stretched out perilously long — estimates are that it surpassed 15 km (9 miles), and was

perhaps as long as 20 km (12 miles). It was then suddenly attacked by Germanic warriors who were carrying some light

swords, large lances and spears called fremae in Germanic language that came with short and narrow blades,

so sharp and warrior friendly that they could be used as required. The Germanic warriors surrounded the entire

Roman army and rained down javelins on the intruders.

Otto Albert Koch: The Battle of Varus, 1909

Otto Albert Koch: The Battle of Varus, 1909

The attack out of the undergrowth came unexpectedly for the Romans. The Germanic soldiers attacked with all their

might. The resistance of the Romans was hindered by the terrain. It was impossible to organise a battle formation.

In addition, the impedimenta with its civilians, wagons, pack animals and the transportation carts had to be protected.

Therefore, the loss and the casualties were high. In the evening, they entrenched themselves behind a carefully set

up camp. They discussed their options and decided to leave unnecessary ballast behind, especially the transportation

carts. They set everything on fire so it would not fall into the hands of the enemy.

The second day was no better for the Roman side despite strategic considerations. In addition, the weather was

persistently bad. As the paths became sodden and the approaching enemies continued their incalculable attacks,

the Romans suffered heavier losses than before. An orderly camp for the night was impossible. The Romans tried to

defend themselves as good as possible. - Were these the forces that had also attacked the Germanic people who had

sent for help? Could the Romans, if they pushed forward, join them? And where was Arminius, who had left two days earlier to call on allies for help?

Well, Arminius surely had to laugh. Being a trained Roman soldier, he understood Roman tactics very well and could direct

his troops to counter them effectively, using locally superior numbers against the dispersed Roman legions. The

Romans managed to set up a fortified night camp, and the next morning broke out into the open country north of the

Wiehen Hills, near the modern town of Ostercappeln. The break-out cost them heavy losses, as did a further attempt

to escape by marching through another forested area, with the torrential rains continuing. The rain prevented them

from using their bows because sinew strings become slack when wet, and rendered them virtually defenseless as

their shields also became waterlogged.

The Romans then undertook a night march to escape, but marched into another trap that Arminius had set, at the foot

of Kalkriese Hill (near Osnabrück). There, the sandy, open strip on which the Romans could march easily was

constricted by the hill, so that there was a gap of only about 100 m between the woods and the swampland at the edge of

the Great Bog. Moreover, the road was blocked by a trench, and, towards the forest, an earthen wall had been built along

the roadside, permitting the Germanic tribesmen to attack the Romans from cover. The Romans made a desperate

attempt to storm the wall, but failed, and the highest-ranking officer next to Varus, Legatus Numonius

Vala, abandoned the troops by riding off with the cavalry; however, he too was overtaken by the Germanic cavalry

and killed. The Germanic warriors then stormed the field and slaughtered the disintegrating Roman forces.

Reconstruction of the improvised fortifications prepared by the

Germanic tribes for the final phase of the Varus battle near

Kalkriese

Reconstruction of the improvised fortifications prepared by the

Germanic tribes for the final phase of the Varus battle near

Kalkriese

When Varus realised the hopelessness of the situation he committed suicide. Thereby the survivors lost courage even

more and many tried to flee, while others surrendered to the enemy or committed suicide, too.

Around 15,000–20,000 Roman soldiers must have died; not only Varus, but also many of his officers are said to

have taken their own lives by falling on their swords in the approved manner. Tacitus wrote that many officers

were sacrificed by the Germanic forces as part of their indigenous religious ceremonies, cooked in pots and their

bones used for rituals. However, others were ransomed, and some of the common soldiers appear to have been

enslaved.

All Roman accounts stress the completeness of the Roman defeat. The finds at Kalkriese, where, along with 6,000

pieces (largely scraps) of Roman equipment, there is only one single item — part of a spur — that is clearly Germanic

would seem to indicate minimal Germanic losses. However it must be taken into account that the Germanic victors

would have removed the bodies of their fallen, and their practice of burying their own dead warriors' battle gear with

them must have contributed to the lack of Germanic relics. Additionally, several thousand Germanic soldiers were

deserting militiamen who wore Roman armour (which would thus show up as "Roman" in the archaeological digs);

and in fact the Germanic tribes wore less metal and more perishable organic material.

A Roman Mask found at Kalkriese

A Roman Mask found at Kalkriese

The victory over the legions was followed by a clean sweep of all Roman forts, garrisons and cities — of which

there were at least two — east of the Rhine; the remaining two Roman legions, commanded by Varus' nephew

Lucius Nonius Asprenas, were content to try to hold that river. One fort (or possibly city), Aliso, fended off the

Germanic tribes for many weeks, perhaps a few months, before the garrison, which included survivors of the

Teutoburg Forest, successfully broke out under their commander Lucius Caedicius and reached the Rhine.

Upon hearing of the defeat, the Emperor Augustus, according to the Roman historian Suetonius in his work

De vita Caesarum ("On the Life of the Caesars"), was so shaken by the news that he stood butting his

head against the walls of his palace, repeatedly shouting:

"Quintili Vare, legiones redde!“ ('Quintilius Varus, give me back

my legions!')

The three legion numbers were never used again by the Romans after this defeat!

The battle abruptly ended the period of triumphant Roman expansion that had followed the end of the Civil Wars

40 years earlier. Augustus' stepson Tiberius took effective control, and prepared for the continuation of the war.

Legio II Augusta, XX Valeria Victrix, and XIII Gemina were sent to the Rhine to replace the lost legions.

Arminius immediately sent Varus' severed head to Maroboduus, king of the Marcomanni, the other most powerful

Germanic ruler with the offer of an anti-Roman alliance. Marbod declined the offer, sending the head on to Rome for

burial, and remained neutral throughout the ensuing war. Only thereafter did a brief, inconclusive war break out

between the two Germanic leaders.

Romes answer..

Augustus asked himself whether Germania was worth the effort and how far one should go. His first action was

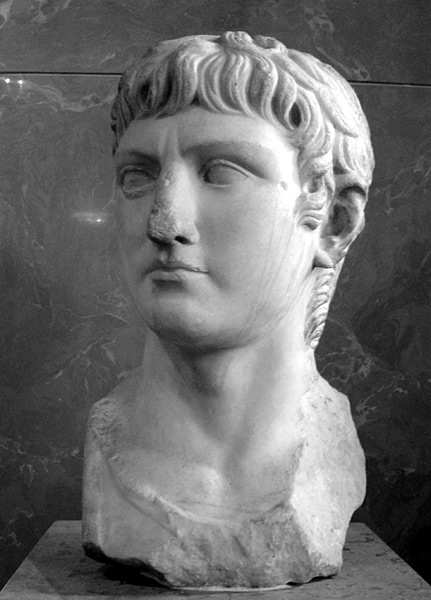

to send Tiberius to take command at the river Rhine. Tiberius along with Germanicus arrived in Germania in 10 AD.

In the following year more battles took place. The Germanic troops did not seem to make any concessions.

In 12 AD Tiberius was granted celebrations in Rome on the occasion of the Pannonian victory.

In 14 AD Emperor Augustus died unexpectedly. His adopted stepson Tiberius was appointed as his successor.

Tiberius continued to employ Germanicus in the troubled "province" in the north. Germanicus along with Caecina Severus

left the Rhine to enter further into Germania in 15 AD. Germanicus passed through the land of the Chatti and

subdued them. He then went to help the pro-Roman Cheruscan Segestes who was besieged and had called for help.

In the course of his liberation Thusnelda, Arminius' pregnant wife - and the daughter of Segestes himself, fell into

the hands of the Romans. They took her to Rome as a prisoner.

Germanicus

Germanicus

When Germanicus arrived at the place of the Varus Battle, he told his men to collect and then bury the soldiers'

mortal remains which were still lying around. They did not have a lot of time for this because the Germanic troops

were already attacking again. Consequently, the retreat from Germania was difficult and many soldiers were injured

or lost their lives.

Germanicus, however, did not acknowledge defeat and returned to Germania with his army and an armed transport fleet.

Once again, there was a tough battle with a high number of casualties. The situation was worsened by severe autumn

storms during the retreat. Nevertheless, Germanicus was able to recapture two of the legions' aquilas which had been

seized during the Varus Battle. Emperor Tiberius was of the opinion that further action in Germania would be

pointless and therefore relieved Germanicus permanently from office in 16 AD. In spite of the dubious victories in

Germania, a triumph was organised in honour of Germanicus in the following year.

Cheruscan prisoners, like Arminius' wife and his little son, who was born in captivity, were paraded through

the streets of Rome. The historian Strabon also mentions the presence of Thusnelda's father Segestes who participated

as an official guest, loyal to the Roman Empire. He watched as his daughter, his grandson and further Germanic

hostages known to him were paraded.

Was he happy? We don't know...

The Romans subsequently retreated to the Rhine and concentrated on securing this border. However, there were

still many contacts between the Romans and the Germanic tribes, e.g. through trading. The Romans were no longer

interested anymore in conquering the Germanic regions on the eastern side of the Rhine: The anticipated benefit

was not worth the effort and trouble.

The Myth Arminius - Hermann

Since the 16th century, the image of a typical Germanic man was utilised to convey contemporary political issues

and, at the same time, to create a related atmosphere which expressed a long - and justifying - tradition.

It was rather the contemporary imagination and fashions which influenced the way the Germanic people were perceived,

rather than scientifically based knowledge about their way of living, their clothes et cetera.

The first illustrations of the Germanic people - which were widely spread and which influenced the subsequent

art - significantly do not originate from the Germanic people but from Roman artists. They manifested their view

of the tribes in the North of the Empire who were either supposed to be conquered or were already allies.

Thus they created a repertoire of forms which was later taken up again or changed. In these illustrations,

the Germanic people were usually presented as the vanquished. They were obviously non-Romans apparent in their

clothing and hairstyle. In view of the much cited fact that they were either naked or just partly dressed,

they seemed to be not only "barbaric", but also strong and serious opponents.

It was deemed a military success - worthy of celebrating a victory march - to defeat these enemies.

After the decline of the Roman Empire, the image of the Germanic people did not play such an important role in

medieval times. Only when Tacitus' "Germania" and his "Annals" were printed again at the end of the 15th century

the Germanic people were remembered as the opponents of the Roman Empire. This awakened the alleged descendants's

interest. Subsequently, the rebellious Cheruscan was uniformly and positively appreciated which shows how willingly

and uncritically these texts were perceived. In his "Annals", Tacitus celebrated Arminius as the "liberator of

Germania" who had been courageous enough to "challenge the Roman Empire which was in full bloom".

According to him, he was "not always victorious in particular battles, but undefeated in war".

He was therefore a real hero and one expected that emulating him would bring honour.

In this manner the figure "Arminius" - Martin Luther presumably named him "Hermann" - started to appear in

literature and its illustrations in the 16th century. Arminius' character was used both as an educational example

and as a model which could be associated with apparently comparable political, contemporary situations.

The Cheruscan was presented in book illustrations wearing a traditional costume of the 16th century.

Small invented details or inscriptions were added to reveal his Germanic identity. The threatening Romans would

either represent an oppressing territorial lord or the pope, against whom one had to defend one's interests.

Arminius appears as a Free Imperial Knight equipped with contemporary armour in Burchard Waldis' "rhymed chronicle".

Just like David who carries Goliath's disembodied head, Arminius holds the hairs of Varus' head in his right hand

while raising the bare sword with his left hand.

Together with eleven other, mostly invented heroes of the German history, he is part of a gallery of characters

who personify the undivided unity of the German Empire. They were supposed to remind the quarrelling territorial

lords of the German Empire and how important the unity was, especially when faced with the menacing Turkish conquest.

The first part of Daniel Caspar Lohenstein's novel "Arminius und Thusnelda" was published in 1689.

Roman and Germanic people are displayed in the illustrations made by Johann Jacob von Sandrart. They wear fanciful

costumes which were either based on the Roman historians' descriptions or which imaginatively added detail to the

unknown. A winged helmet often appears in this context as a Germanic characteristic. A "Germanic leader" had worn

this helmet on an illustration made by Simon de Vries' in 1616. Since the 17th century, it developed to be

the most-cited Germanic characteristic in the following centuries, although there is no historic basis for this detail.

Lohenstein's novel was dedicated to King Leopold I. who was probably impersonated in the hero of the novel.

The contemporary noble readers apparently seemed to take a fancy to the dedication, "In honour of the German nobility

and to their laudable successors" as well as to the exotic, entertaining style of his baroque illustrations.

After 42 years a second edition was published. In 1772 the Fürstenberg porcelain manufacture produced a series of

Germanic figurines which imitated the above-mentioned illustrations.

A range of dramas, operas, songs and poems which dealt with Arminius' fight against the Romans were released in

the second half of the 18th century. They particularly focused on the position of the aristocrats - Arminius was

also considered to have been noble - in contrast to their subjects. This distance was clearly expressed in the

contemporary illustrations. The common people had plain, sometimes even poor clothes, whereas their leader's

clothing demonstrated courtly splendour. In addition to this, their lowly position in the tribal society was

expressed by illustrating a genuflection or a bowed back.

In order to strengthen the position of the territorial lords, the emphasis was put on the aristocratic supremacy

which seemingly was based on a long tradition since the early Germanic days. Optionally, Arminius could either be

interpreted as a liberator and unifying personality of the Germanic tribes, or as an appeal to strengthen the

Habsburg Imperial power - or the power of an ambitious prince like Frederick the Great of Prussia. A different

view appeared simultaneously to this interpretation of the events. The illustrations in Klopstock's

"Hermanns Schlacht" put on stage by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki in 1782 show - in accordance with the

description - an Arminius-Hermann who is capable of prioritising the virtue of love for children as opposed to his

heroism and who thereby provided a potential identification for the bourgeoisie. Pictures which represented this

fundamental idea would show an Arminius who did not externally differ from his followers. The former great distance

was succeeded by a new closeness which made it easier to empathise with the hero.

In 1782 Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder illustrated a noble Arminius holding court. In contrast to this,

Wilhelm Tischbein interpreted Arminius as a devoted family father wearing rather plain clothes, who - with his chin

raised - defends his wife, children and father with an uplifted sword and a protecting shield against an invisible

danger. This matched the basic feeling of the Biedermeier time when people withdrew to their private lives after

belligerent periods.

At the end of the 19th century, at the time of the foundation of Bismarck's German Empire, the illustration of the

subject changed fundamentally. Unlike the previously favoured scenes with selected individuals, epical pictures

of battles occurred. They would decorate public buildings and were supposed to pedagogically celebrate the

"birth of the nation" by providing the necessary historical basis.

The completion of the Hermann monument in Detmold in the year 1875 is also due to the foundation of the Empire.

Without the latter, there probably would not have been an initiative to raise the much-needed funds.

The inauguration ceremony was a homage to the absolutistic Wilhelmine Imperial House. The commemorative plaque

for William I. manifested the monarch's identification with the monumentally inflated "national hero"

who raised his sword towards the "French hereditary enemy".

The Hermann monument in Detmold around 1900

The Hermann monument in Detmold around 1900

At the time of the National Socialism (1933 - 1945), the state and the leading party were particularly interested

in the Germanic history. It was idealised and exploited in order to provide a destination for those who were looking

for an identity and a legitimacy. The rulers even tried to revitalise the self-created founding myth and the

system which allegedly was behind it. I.e. they built "Thing" places and unsuccessfully invited the population to use

them, in a Germanic style, for theatre plays and choral events, et cetera. The myth itself continued to be a means

to an end. Pictures were also utilised. Hermann, mostly in the shape of the Hermann memorial, could be seen on

postcards with ideologic slogans or on the front pages of National Socialist societies. The purpose was to put

their own actions into a traditional context by referring to history.

After the break-up of National Socialism the Hermann myth did not play a significant role anymore.

The only Germanic figures which appeared were comic characters and Asterix the Gaul could easily cope with these.

They could also be seen on paper bags from bakeries, with croissant helmets on their heads and raising baguettes

rather than swords for advertising purposes. Hermann had to leave the political sphere and was sent back to science.

He regained his traditional name "Arminius". Political connotation has obviously gone; emancipation from the

clutches of the early days seems to have been successful.

However, he was a guy who made history - and he made it near my hometown!